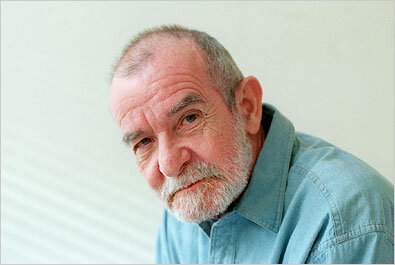

Athol Fugard: Art Battling Apartheid and AIDS

Athol Fugard is a novelist, actor, director and first and foremost, one of the great playwrights in the world today. His roots in the Karoo, the arid, topographically unique landscape of South Africa, deeply inform his work. Fugard’s compassion for his characters is laced with a rage against the injustice of apartheid, a topic never polemical but always part of his lyrical plays like Blood Knot, Master Harold and the Boys, Sizwe Bansi Is Dead and Tsotsi, the Oscar-winning film based on his novel.

His work, despite threats from the government, eventually helped extend to the world a recognition of South African racist policies and the strengths and failures of the common people living under those policies. His latest play, Coming Home, currently at the theater he regularly calls home, the Fountain Theatre in Hollywood, addresses the newer South African scourge — AIDS. The London Telegraph, in a November 2008 story, estimates that more than 330,000 South Africans have died of AIDS due to the government refusing anti-retroviral drugs. Avert.org claimed that as of 2007, there were 1000 deaths a day and 5.8 million people living in South Africa with HIV.

Fugard’s indignation at the wrongs of the world is tempered with a humility and graciousness that is truly striking. After a recent performance of Coming Home, he moved the audience with an impassioned talkback about the failures of his homeland and his love for the theater. Below is an edited portion of our conversation on the phone, July 29, 2008:

BS: I hope you won’t mind talking a bit about AIDS and the government of South Africa, what has happened there and is happening there now, that influenced you to write this terrific and wonderful play.

AF: There is no question about it, that thanks to the unbelievable idiocy, madness...of our former President Thabo Mbeti, and his Minister of Health, South Africa found itself dealing with a tragedy as great as any served up by the apartheid years...Now some real progress has been made in releasing the anti-retroviral drugs to AIDS sufferers but even so, this battle against our pandemic is far from over. Because you know it’s not just a question of the finances involved, but we’re up against a traditional culture which at some level resists the wisdom of the scientists. It’s a very complex and a very difficult situation. But as I say, it has improved but nowhere near enough yet for us to say we’re on top of it.

BS: I want ask you about a more positive aspect of South Africa and your love of the Karoo. You said at the talkback at the Fountain Theatre that you tend to do your writing when you go back to South Africa.

AF: That is true. More importantly than just doing the writing there, I find my stories there. You know, when I’m among my people, when I’m speaking my mother’s language, because my mother spoke good English but she wasn’t English. She was an Afrikaner, one of the Dutch stock, the regional Dutch stock in the country. Which is also the dominant language of that little village in the Karoo where I’ve got my South African home (New Bethesda), which I will be visiting later this year again. I go back once a year.

BS: I’d like to know more about when you were in Johannesberg and were a clerk at the Native Commissioner’s Court, which is something that Americans are not familiar with. I wonder if you describe a bit what that court did and how the cases that were affected by apartheid influenced you.

AF: I think it was one of the most miserable experiences of my life, in that court, where I was clerk of the court.

BS: Really?

AF: Because I really saw at first hand what the policy of apartheid was doing to innocent people. And basically what that court was dealing with, well, let me start by saying during apartheid, all adult men and women were forced to carry something called the passbook...Stamps that the official stamped in that book determined...where you could live, whether you could have your family with you. It controlled your life.

BS: Right.

AF: It controlled your life. And the first thing a white policeman always did when he saw a black man that he didn’t like or that was acting in his opinion suspiciously was to say, “Your book, please.” The court cases that came before the court where I was working dealt with offenses in terms of that book, characters who were in Johannesberg who didn’t have permission, as defined by a stamp...It was something only Kafka could have written about, because we disposed of a human being every two or three minutes. It was like...a lunatic, nightmare G.M. assembly line, where the accused lined up outside the door to the courtroom, in the prison yard and then let in one at a time. And dispatched for times ranging from two weeks, three weeks, two months, and also, you know, thrown out of Johannesberg, sent back after they had served their sentences, into the country where there was no work, no chance of earning a living, where their families were hungry and their children starving. Uh, man, I’m telling you, it was a nightmare. I saw how my country worked.

BS: When you were doing The Blood Knot, with Zakes (Mokae, Tony Award winner for Master Harold), was that the first time you had performed in your work and what was the sensation of saying your own words onstage?

AF: (Laughs.)

BS: That’s rather different for playwrights.

AF: “It’s so long, man. the monologues.” Fortunately, I went on to make sure that they were edited and properly cut.

BS: (Laughs.)

AF: I was a young writer. It sounded like from the typical young writer’s drawer or whatever. It was hideously overwritten.

BS: (Laughs.)

AF: I mean, you so enjoy your language. Any little thing that comes up in the course of writing the play and you go up to write a couple of pages about it, you know.

BS: (Laughs.)

AF: And that happened with me.

BS: Did it change the way your wrote?

AF: Doing it with Zakes, you see, I never fancied myself as an actor. I’ve never fancied myself as a director. I think I’ve said this. My essential identity is that of a writer. But the plays I was writing, the stories I wanted to tell, nobody else in South Africa would touch with a bloody march pole. It was an incredibly jingoistic society. If you didn’t look like George Bernard Shaw or didn’t make you laugh like Oscar Wilde, it wasn’t set for the South African stage. And other playwrights of that time were writing plays like that, that had nothing, nothing to do with the urgent and terrifying reality of the millions of black people alive in that country at the same time. But they weren’t interested. “Good God, the black man and the white man together on the stage at the same time, living in a shack? What sort of story is that? Disgusting. That’s kitchen sink drama. Worse than kitchen sink because there’s no kitchen sink!”

BS: (Laughs.) I understand that, regarding Boesman and Lena, that an early production, if not the first production in South Africa, had whites playing black characters. Is that true and what was the reaction?

AF: I played Boesman because there were no actors available for roles of that dimension at the time. A great, not extraordinary, a great South African actress called Yvonne Bryceland, who I worked together with for 21 years, played Lena. At that point, also, apartheid was very much a reality in South Africa and so the character of the old black man who runs shuffling into their lives out of the darkness, I wouldn’t have been allowed to put a real black man onstage because by then, laws had been passed outlawing mixed casts on the stage.

BS: Did you actually rewrite The Island while it was in production based on audience reactions?

AF: No...There was a final edited version in the rehearsal room. They would improvise. I would go home after the rehearsal and I would—because improvisation has got to be very severely disciplined or it just runs away with itself—I would do that disciplining and come back the next day with a scene I typed out for John (Kani) and Winston (Ntshona) and that’s then how we went to work.

BS: I read that in the beginning, they had some sort of blanket or towel and they kept making it smaller and smaller to give the sense of being in prison on Robben Island (where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned).

AF: That’s right.

BS: And it’s my understanding that the government could not shut down the play because there was no existing manuscript.

AF: Of course not. I hid the text away. There was very distantly an existing manuscript. But in much the same way that poetry of the great Russian poets during the Stalin era were on secret bits of paper, or committed to memory so that censorship could not get hold of him and so that Stalin couldn’t get hold of him, we learned that lesson from them. And we just made sure, oh yeah, there were copies of the play all right, but they were in places and with people the Special Branch would never find.

BS: Did the government attend any of the performances?

AF: Oh, every one. (Laughs.) Oh, yeah, the Special Branch was the enforcement. You got to know them. You’d greet them. “You chaps pay for your tickets tonight? Or do you want freebies?” (Laughs.)

BS: (Laughs.) That’s fascinating. And yet, they did not close down that production, despite their fear?

AF: They threatened us.

BS: Yes?

AF: But we made very certain of our circumstances. There were loopholes in the law. And we had lawyers, very good, courageous lawyers—as was the case with the civil rights battles in the South—who knew the law and knew what loopholes were there. We exploited those loopholes, making the performance allegedly private.

BS: Ah.

AF: Invited friends and family, you know what I mean?

(This piece, honored by the Los Angeles Press Club, originally appeared in Huffington Post.)